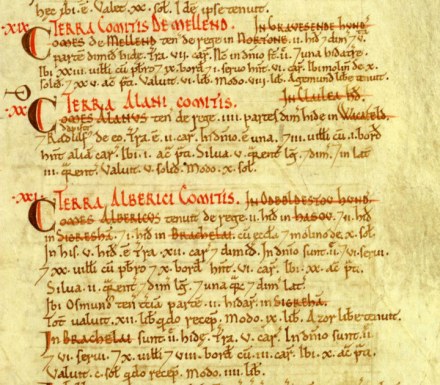

The Domesday Book of 1086 was the most wide-ranging and thorough study of its time – and desperately unpopular with the people upon whom taxes would be levied on the basis of their recorded holdings. With details of 13,418 places copied onto parchment, no other piece of European medieval demography comes close, and scholars continue to find it valuable more than nine hundred years on.

To mark the 9th centenary of the work’s completion back in 1986 a new, multimedia edition of Domesday was compiled over a two-year period, in which people – mostly children from more than 9,000 schools – wrote about their lives, and their part of the country. The whole nation was subdivided into 3km x 4km blocks, any of which could include photos and text, and in some cases movies. Schools and other interested parties got a BBC Master computer and a Philips VP415 “Domesday Player” so that they could access the information held on special-format LaserDiscs – a precursor to the DVD that stored a “massive” 324MB of data on each side of a 30cm disc. (There was a ‘Community’ disc and a ‘National’ disc; nowadays the whole thing could fit many times over on the cheapest USB flash drive still made.)

It’s a great little piece of history. Despite the low-resolution, amateur photographs and writing to match, it’s a snapshot in time, and it can be very interesting to look through and remember how things were.

But we nearly lost it.

The technology that had been used for the BBC Domesday Project was a snapshot in time as well. As the 21st century dawned, few people still had access to a BBC Master computer in working condition, and Philips VP415 disc readers were rarer still. Because the project had used custom formats in both software and hardware (pushing the boundaries of what could be achieved in the mid-1980s) this was no mere file format issue. Domesday had stored each image as a single frame of analogue video, with an overlaid user interface, and this was a difficult mess to untangle.

The original Domesday Book had survived nine hundred years, becoming more durable after 1861 when a scholar would most likely have worked from a photographic reproduction. The information in the new Domesday Project, for all its technological ingenuity, didn’t manage fifteen years before it was for all practical purposes inaccessible.

A heroic effort by several groups secured a more future-proofed version of the work, basically by recreating it: tracking down master copies of information held on a 1-inch videotape format, writing emulation software that allowed a modern computer to interface with a VP415 “Domesday Player” and so on. In 2011, a BBC initiative led to much (but not all) of the Community disc being published on the Internet. Copyright issues mean that the full contents of the Domesday Project are unlikely to be made available before 2090 – although perhaps one might hope for publication in 2086, in time for the 1,000th anniversary of the original.

Digital obsolescence is a terrible shame. It’s bad enough that we throw away tens of millions of computers every year; how much worse to think that we might be throwing away everything that we did with them as well! You might recall how a collection of work by Andy Warhol was found on a stash of floppy discs and ‘rescued’ last year…

This isn’t just a problem affecting overlooked bits and pieces of culture: businesses are fighting an ongoing battle against digital obsolescence as well. Imagine making and supporting long-lived systems such as a ship, or a power station: the design information you might need to look up will have been through half a dozen processes of translation, from when the design was executed on a mainframe computer, and then converted for access on minis, on DOS-based machines, and then various versions of Windows. The design software, as well as the operating system, will likely have changed. Translations of 3D geometry are notoriously unreliable, particularly where bezier patches were used to define surface shape, which means it can become very difficult to manufacture new parts. Do you translate your files and hope for the best, or do you try to keep your 1970s era mainframe in working order? There are no good answers.

I’ve recently converted my PhD thesis into a modern format. (We weren’t required to provide an electronic submission, back in my day…) The process required computers of three different vintages, and quite a lot of laborious copying and pasting. The thesis had been written on a Power Macintosh 5500/275, a machine I’d bought in 1998 – the year they were discontinued. It had long since gone for recycling, but the good old 5500 had featured a SCSI port (now a long-obsolete interconnection standard) which had allowed me to make backups. After all that work, you can bet I made a lot of backups!

My word processor of choice back then was part of a suite of office tools called ClarisWorks – long since discontinued. Modern software such as Pages and Word refused to open my ClarisWorks files, but a quick search of the Internet revealed that others were using a free package called LibreOffice to open all kinds of obsolete file formats. I used this as an interim stage to get the text into my word processor of choice.

That got me the text, but not the images. These required a different approach, and had to be brought in individually, via an aged laptop that had fortunately been bundled with “AppleWorks 6”, which marked the swan song of the Claris tools before Apple killed them off. (I keep that laptop around because my latest machine doesn’t have an optical drive – another format that’s rapidly heading for the dustbin of history.)

All was well until I reached Appendix 3. In the print copy this had been a collection of images from a Powerpoint presentation, dating back to 1994. I’m nerdy enough to own a USB floppy disc drive, so accessing the physical media wasn’t a problem… but did Microsoft Powerpoint deign to open a Powerpoint presentation from twenty-one years ago? Hell, no. Nothing I still owned would touch it. Help came from Zamzar, who offer free online file conversion. Fortunately, I wasn’t trying to convert anything confidential, so I could use a web-based service. My first attempt failed, but then I managed to convert the old .ppt file to an interim format from around 1997, which was acceptable to modern Powerpoint, and Appendix 3 was rescued.

Like the BBC Domesday Project in miniature, only fifteen years had passed but my work required quite a bit of human intervention to make it accessible again. (And let’s be honest, only the author would care enough to undertake the job.) This must be happening to information all over the world, all the time – and you can be sure it’s going to keep on happening.

It’s alarming, quite frankly, to discover how easy it is for a piece of work that you once spent weeks or months on to disappear into oblivion. When the VIVACE Project ended in early 2008, for example, we all patted ourselves on the back, secure in the knowledge that the hosting for the project website was all paid up for the next five years and all the public project reports would continue to be available.

Five years seemed like ages; long enough, surely, for everyone to get what they need from the project. Well, apparently not; I’ve had to trawl through snapshots made by the Wayback Machine, an Internet archiving tool, in order to find copies of my own work.

A project ends, and you move to a new job. Obviously, you don’t get to take your computer with you. Meanwhile, you upgrade to a new computer at home, or maybe suffer a hard drive failure… and the next time you want to draw upon some old piece of work, you can’t find it. Or perhaps, as above, you can find it but you can’t open it. In the case of VIVACE, this was a project funded with €50m of taxpayers’ money, plus money from industry: to think that some of the things we discovered might be effectively gone less than a decade later is alarming.

Of course, they might well still exist on some obscure disk in a personal collection, as a printout on a library shelf or in a filing cabinet somewhere, but this is the 21st century and we expect our information to be only a mouse click away. If it can’t be found instantly we assume it doesn’t exist. (Students, I’m looking at you…) Also, there’s the danger that anything that’s hard to find is likely to become ever more obscured over time, as the output of still more documents buries the older information.

This should be of concern to those who care about sustainability. Health, clean air, decent drinking water… they’re important, but we’re not here simply to survive and raise families. Rabbits can do that. I feel that humanity ought to create something with intellectual or artistic merit. Sustainability demands doing things with an eye on the future, and building to last – but if this is the Information Age, why isn’t our information built to last?

A digital copy of your PhD thesis! Happy memories of CAL3P :-)

Yes indeed… now available on the Salford University institutional repository, via http://usir.salford.ac.uk/34320/ – not sure the CAL3P software itself would run on Windows 8!

Pingback: Sustainable Infrastructure… through Archaeology | Capacify

And… I had to do still more digital archaeology, because Salford University changed their repository. (Which just goes to show that digital information really isn’t safe.) New link, found after a brief struggle… https://salford-repository.worktribe.com/output/1417733/use-of-multimedia-in-engineering-education