Back in January 2016, I wrote a supply chain case study about a company called WayTools and their ‘TextBlade’ miniature keyboard. Since the case study is essentially about the non-appearance of a product, at that time about a year late, I thought that I might be able to use it once or twice before events overtook me, with WayTools silencing all the doubters by bringing their product to market at last.

Some customers, having paid $99 for a product that was supposed to be out within a month, have as I write this (January 2017) been waiting almost two years. They weren’t signing up to a kickstarter project: the gadget was presented as a finished design, ready for volume production.

The various problems that WayTools reported (via their corporate blog, and in a user community forum) made it very useful as a case study showing some of the things that can go wrong, both internally and in the supply chain. It became the subject of a couple of our exam papers, but I never expected that I’d still be talking about WayTools’ failure to deliver the product as 2017 rolled in.

You can download a copy of the case study here.

Two years is a long time in the technology sphere: mobile devices and the way we use them might have changed a lot in that time. WayTools have been fortunate that there have been no really big advances. For the most part, Apple users still contend with the woeful Siri, which means that natural speech isn’t about to replace the keyboard anytime soon… but there are newer and better kids on the block. Cortana, Google Now, Assistant.ai, and Viv all want to help users to get things done without typing. Meanwhile, the iPad pro has appeared, with a pretty good keyboard of its own – essentially copying that found on Microsoft’s Surface Pro. Since these are built into the protective screen cover, they don’t occupy much space. Is there still a market for a tiny-teeny keyboard, nowadays? WayTools think so, and (as far as we know) they’re still doggedly plugging away at refining their product.

An urge to make the best keyboard they possibly can appears to have been the main problem. In May 2015, they reported that they’d replaced the nylon ‘butterflies’ under each key with liquid crystal polymer, improving the feel and durability of the keyboard. That’s commendable, except that people who had ordered one had expected to receive it months before. What was wrong with simply making in quantity the product that the tech journalists had enthused about, back in January 2015? Why not hold off on any improvements until the “mark 1” product had been delivered, generating a few hundred thousand dollars in revenue?

The new, stronger ‘butterflies’ were found to cause defects during the assembly stage, and a new fixture had to be designed as a work-around… and so on, and so on. Right up until the present, as far as I can tell. A few customers have been invited to join the Test Release Group (‘TREG’) and they have received sample units, but there’s still no sign of order fulfilment being achieved.

I think we can all agree that introducing a years-long delay while you take something that was seen to work and then ‘improving’ it until it doesn’t is a distinctly unusual business practice. (Some in the community voice the opinion that the TextBlade can’t appear as a commercial product while certain patents are in place, and that this is fundamentally about patent wrangling and not about little keyboards at all.)

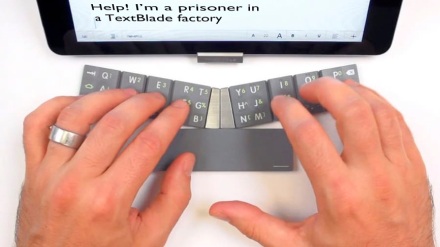

By the time of writing, some customers had been waiting to see this for almost two years. [image: mcttrainingconsultant]

I have no axe to grind: I’m not out of pocket by $99. I wanted a TextBlade, sure enough… but I decided to wait and see. Thus far, it’s been all waiting and no seeing, but that’s actually a good thing. I wanted a TextBlade… but I didn’t really need one. It would have been fun to pose with one in meetings and on flights, but I can’t point to any particular job that didn’t get done since 2016 and say that’s because I didn’t have a miniature keyboard to use with my iPad.

When I write about the sustainable supply chain, perhaps I focus too much on the supply side. A big part of being ‘green’ isn’t about shopping for products that are made from sustainable materials, or products with low energy consumption: it’s about doing without. It’s about recognising that what you have will do, and perhaps paying off your debts instead of buying more stuff that you don’t really need. It’s taken me two years to realise it, but WayTools and I won’t be doing business, even if they were to announce tomorrow that they’ve just landed a container-load of TextBlades at Felixstowe, with all quality problems finally addressed and next-day delivery guaranteed. I’ve coped perfectly well without, and I know that I can continue to do so.

You may think that $99 is a bit pricey for a keyboard, nowadays, but one school of thought holds that buying expensive things can actually be quite ‘green’ (unless precious metals are involved). Better that you should buy a single, high-priced item than buy a whole bundle of less expensive items, embodying more materials, requiring more logistics, perhaps being less durable, and ultimately representing more waste at the end-of-life. Smart consumption requires that we understand that cheap stuff isn’t necessarily good for us.

My TextBlade journey has turned out to be very inexpensive and very ‘green’ indeed. If it had really existed when it was first launched, I think I would have bought one. By now, the novelty would have worn off and the product might have worn out… and even if it still worked just fine, the industrial design of the TextBlade is looking a bit long in the tooth, now. But instead of being a disillusioned customer, I still have my $99, no resources have been wasted (other than whatever is consumed in web browsing) and I’ve reached an endpoint where I no longer feel that I lack a little keyboard.

TextBlade customers have been remarkably patient, considering. Their good-natured humour at each delay has been kinder than the manufacturer really deserves at this point. Even the Twitter bot called @Failtools that sent out a regular ‘status update’ in the style of WayTools’ own news bulletins (now suspended by Twitter, sadly) had a certain bitter humour about it – and delivered a salutary lesson on the subject of public relations in the Internet era.

Some good things are worth waiting for, without a doubt. Glowforge comes to mind: a desktop laser cutter/engraver that’s been delayed more than once. Consider me very interested, but not enough to actually bankroll the development process. Sometimes, the expectation is simply greater than the reality. That’s a consequence of effective marketing, but perhaps virtual products that never arrive offer a new form of gratification, where you get all the excitement and expectation, and never face the disappointment that comes with actual ownership.

It’s certainly worked for me.

(Also, I got a case study out of this. Thank you, WayTools.)

Update: it’s December 2019, and as we approach the four-year mark I think it’s clear that if WayTools were in any way able to deliver this product, it would have reached the market by now. A Google search reveals that much of the remaining speculation about the TextBlade is now centred upon the theory that WayTools never intended to deliver the product as such, but were hoping to generate some buzz and then allow the company to be acquired by a bigger fish. This makes sense, particularly if the rumour that WayTools don’t hold a key patent is true: that they can deliver endless test items, but they can’t sell a TextBlade for money, for fear of being found to have infringed said patent.

So it looks like this fun exploration of a supply chain that never was is at an end. If reading the comments section below, please note that a lot of the posts that encourage the reader to buy a TextBlade or to give WayTools more time were made from a single account, e.g. by same person – quite likely a person in WayTools’ employ. (Welcome to the era of “fake news…”)