The watchword for UK educators, nowadays, is employability. We need to ensure that our students have better prospects as a result of the time they spent with us (not least because of debts that they commonly acquire during their studies) but how do you prepare a student for a career as a supply chain professional?

The Very Enterprising Community Interest Company think they have the answer – along with a pretty silly name, obviously – and their solution is an educational board game, Business on the Move.

Will we end up calling it BOTM, for short? Not on this blog… but school kids everywhere probably just started sniggering.

Every once in a while there’s an article (e.g., this one) in which those in the know fret that children didn’t know where their food came from. Inner city kids are horrified that eggs come out of a chicken’s backside, that vegetables grow in mud and so on. Trouble is, it’s not just food: young people are hazy on where manufactured goods come from, too – and how they are made to arrive. That’s where Business on the Move comes in: the game’s creators (Andy Page and Patricia Smedley) have used it with children as young as nine, which is pretty clever when you consider the complexity of the real-life systems that it represents.

Planes, trains and automobiles. Oh – and ships.

This is a big game, in a big box that’s bursting with supply chainy goodness! Literally, in the case of my copy, which was damaged in transit. Plumbers have leaky taps; supply chain professionals have bad logistics. In fact, the whole game is an embodiment of the global supply chain that it describes: a sticker on the edge of my box reports that it was made in Ningbo, China (a quick shout out to old friends at the University of Nottingham in Ningbo…) so the game was imported in just the same way that the little counters on the board make their way from China to the UK.

My copy of Business on the Move arrived somewhat scrambled, but the game box was the only casualty. With a somewhat squishy box measuring 61cm by 44cm, this isn’t a game that I’m going to be taking with me to Botswana on teaching trips.

In Business on the Move, virtually everything comes from China. There is a single domestic manufacturer, “the UK Factory” on the board but it comes into play only rarely, on the turn of a card. That’s a little unfair because UK manufacturing has grown tremendously in productivity: the “decline” of British manufacturing has really only been one of employment – not output.

At this point, let’s have a look at what you get for £60, plus shipping. The first thing we have to do is pause for a giggle at the world map that completely omits the Americas. (Are the authors getting the Americans back for the map in Avalon Hill’s ‘

Diplomacy’ – the one that famously refers to the whole of the British Isles as ‘England’?) Beneath the game board, we find a large collection of counters that players of all ages will be itching to play with, featuring containers that fit into trucks and trains – although, sadly, not aboard ships and aircraft.

It’s like Christopher Columbus never sailed west: Business on the Move omits the Americas.

You get a lot of bits and pieces in Business on the Move: probably more that you’ll ever need, which is useful for a classroom setting where a few bits can be lost over time.

In game mechanics, Business on the Move is reminiscent of an old fantasy quest board game called Talisman, in that it features a board with looped, concentric playing areas where the player can choose to move either clockwise or anticlockwise after the dice are thrown. It’s a simple but workable system. In this game the player must declare at the start of their turn that it will be an ‘air and sea turn’, or a ‘road and rail turn’. The fairly simplistic air and sea stage involves bringing containers of goods from China to the UK: aircraft take a direct route and are likely to arrive sooner, but each only delivers a single container’s worth of goods. When a ship arrives in the UK, it delivers three containers of goods.

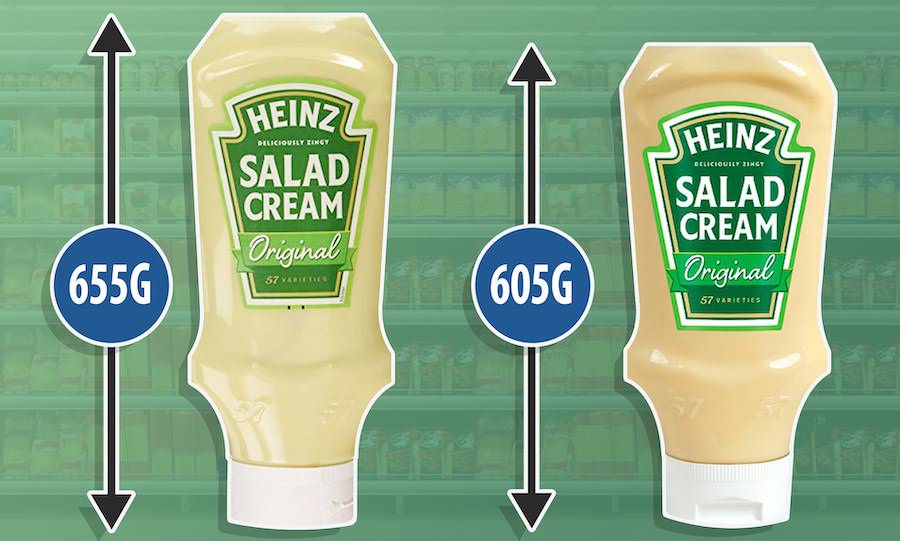

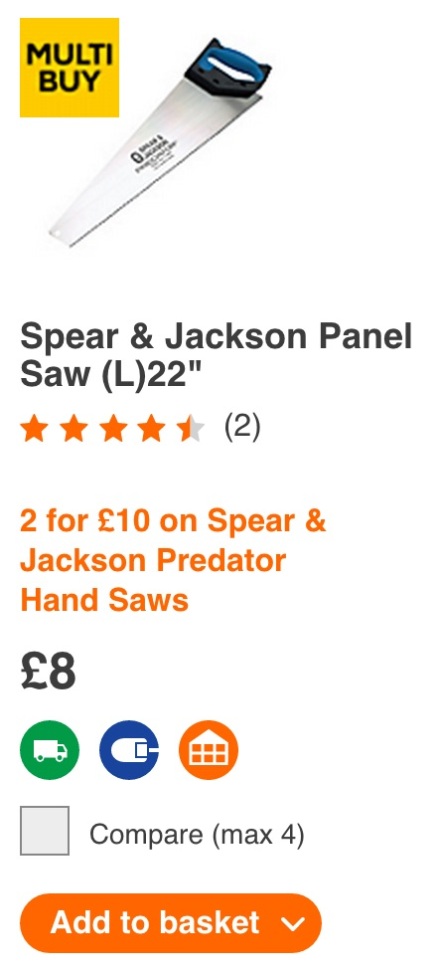

(Yes, the idea that a container ship carries only three times as much as an aircraft is ludicrous, but it’s a game. You’ll need to tell yourself that from time to time as you buy cargo ships for £20,000 and aeroplanes for £30,000, but it’s really no worse than buying Whitehall for £140 in Monopoly, and building a house on it for a hundred quid…)

Having purchased any new vehicles and paid for their upkeep (more on this later…) you’re almost ready to “roll your dice and move your mice”, as board game enthusiasts say. First, you must take a card, and again these are split into ‘air and sea’ or ‘road and rail’. These introduce a random element, detailing events such gridlock on the roads, piracy on the high seas, or the opportunity to buy an extra vehicle at a reduced price. At last it’s time to roll the dice: the number thrown matches the number of vehicles that are eligible to move, up to a maximum of four. All are thrown at once, and the player chooses how to allocate the results between those vehicles.

These aren’t standard dice, however. Instead of generating a number from 1–6, these only go up to five, with an additional result of ‘CO2’ – which is somewhat like rolling a zero. The player is then given the option of paying £5,000 to purchase carbon credits, permitting a result of ‘CO2’ to be re-rolled. It’s a simplistic system – all goods movements are assumed to have the same carbon footprint – but it’s good to see that the contribution logistics makes to climate change isn’t introduced in some game variant or optional rule: it’s built right into the fundamentals of the game.

When a ‘CO2’ result is rolled, the player can pay into a carbon credits system for another chance to move. Later, a player may be able to collect the accumulated carbon credits money.

Players will always begin with an air and sea turn, because all goods start in China. Will you choose to buy pricey aeroplanes with their limited cargo capacity, or will you choose the slower but more capacious ships? Will you buy some of each, reasoning that if certain random events mean that one kind of vehicle is delayed or sent back to base, the other one still has a chance of getting through? This is an example of the strategic decisions that players face as they play through the game. Some such dilemmas aren’t always terribly realistic: after all, most real companies don’t find it necessary to own a vehicle of any sort in order to get a container to the UK: they leave that job to a third party – and pay a bit less than you end up paying in the game, when you take all the risks yourself.

Logistics was never so multimodal as it is in Business on the Move: the Green player is supposedly Eddie Stobart… but this is a parallel universe incarnation of Eddie Stobbart where the company is also a shipping line and/or an airline. It would make more sense if players were able to negotiate deals to carry each other’s cargo, or to have a non-player entity take on some elements of the overall logistic system, but… it’s a game. By forcing players to move goods at both the intercontinental and national level, a more educational experience results.

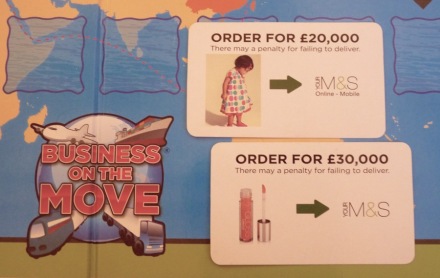

With the goods now sitting at ‘Container Handling’ it’s time to get them on their way to the recipient. A player’s obligations to deliver are shown on cards with the CILT logo: for example, £30,000 will be received for delivering a container of microwaves to Tesco Extra, or £12,000 for delivering cuddly toys to Home Bargains. This is a nice touch because the anonymous container token can become something recognisable, that players feel a connection with. They get a sense of achievement in addition to some money.

Will the player choose to buy a train, or a fleet of trucks? Vehicle pricing continues to be artificial, with a train costing £40,000… and again, who actually buys trains? You’d pick up the ’phone and call Freightliner to get your goods moved, surely?

Rail transport is going to end up with a bad reputation because trains are relatively expensive, and a train only moves twice as much cargo as a truck. They move around the board slightly faster (fewer spaces on the inside track) but this advantage is dissipated by the need to move goods onwards from the railhead with a truck: trains seem like a bit of a bad bargain. Upon each turn, either ‘air and sea’ or ‘road and rail’, players have to pay for the upkeep of all relevant vehicles at £2,000 per vehicle – which includes those that you no longer have a use for. Since goods going overland must complete their journey by road, trains are going to be dead weight at least some of the time, and there’s no mechanism within the rules for selling off an asset that isn’t working well.

The game can be played at varying levels of detail because the rules are split into seven distinct levels: you can get players started quickly and then introduce more realism later. At the most basic level a ship that arrives at ‘UK air and sea terminals’ is immediately converted into three containers, and the vessel is sent to the company base, ready to be reused. There is no requirement to sail back to China… but since the basic game is a race to deliver four containers of goods, there isn’t much more sailing to be done anyway. Some of the simplistic game mechanics are addressed as the level of complexity is ramped up in subsequent games. For example the Monopoly-style business of handling money in the form of high-value banknotes is done away with in later games, in favour of company accounts: this will be great for our module on finance and decision making. At another level comes the opportunity to take “pallet orders” instead of container lots: containers are split into three pallet loads at distribution centres and then sent on for final delivery. With this comes the option of buying into a pallet pooling scheme… or not. Real-life decisions reflected in a board game: excellent!

Some other simplifications remain throughout the game’s seven levels, though. Insurance could have been made interesting, but instead it’s a mere vestigial stub of what it might have been. Buying insurance costs £5,000 regardless of how many vehicles you have and what cargo they might be carrying. Insurance is not per-period but lasts indefinitely, until a claim is made: you hand over the card when you invoke the insurance to avoid certain mishaps. Having handed over the insurance voucher, you’re in the clear. Given that a vehicle costs at least £20,000, the uninsured player would be daft not to renew their insurance at the start of the very next turn. The message that you’d be wise to take out insurance is valid but in a system as simplistic as this, it’s reduced to a no-brainer. (We’ve been teaching a lot more about risk and the value of insurance, just using Monopoly.)

A simplification that I really find it hard to like is that any container can satisfy any one order – there’s no such thing as traceability. If you lose two containers off your ship in a storm, for example, it’s a very non-specific setback. You haven’t lost the consignment of lipgloss, push chairs, laundry detergent, or whatever: you can move any one of your remaining containers to any destination represented on one of your orders cards and collect some money. Thus, on a bad roll of the dice you might still manage to make a short move and declare that the goods have arrived at Home Bargains – or on a good die roll you could forge on up the board towards Marks & Spencer and a more valuable payoff – with the same container. Real life doesn’t work like this. Or have we invented Shroedinger’s shipping container, where the contents are undetermined until it is opened? Fascinating.

I lost some containers, swept off one of my ships in a storm – or would have, but the “i” symbol denotes an event where my insurance can be invoked.

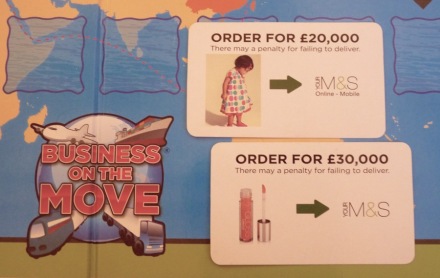

Actually, we need to talk about Marks & Spencer. Clearly, they sponsored the development of the game – just as a lot of organisations did: the game positively drips with logos. That was a good way to fund the game’s development, I suppose, but why were Marks ’n’ Sparks allowed to feature on the board in three places? The distinction between ‘Your M&S’ on the north side of the board and ‘Your M&S Online – Mobile’ on the west side is insufficient – in fact just plain confusing. It could lead to frustrating mistakes, or even accusations of cheating. Perhaps M&S have convinced themselves that they really do have three distinct, strong and popular brands… but it doesn’t work for the purposes of a board game. Fortunately, such a problem is easily remedied with some laser printed stickers: simply replace the indistinct or unfamiliar logos on the board and on the order cards with those of a different organisation. I thought it would be nice to have IKEA in the game: everybody likes IKEA. A lot of the entities represented in the game don’t really have a recognisable brand in the eyes of the common man. If you’re already a supply chain professional you might know who Bisham Consulting are, but for most players the game would be far better if the container of goods went to a well known recipient like Toys ‘R’ Us or B&Q – neither of whom are represented. (You might object that I’m covering up the logos of the sponsors that made Business on the Move possible, in favour of companies that didn’t, but so what? They sponsored the Very Enterprising Community Interest Company – not me and my teaching.)

Weak differentiation between objectives could cause players some frustration.

Before we leave the subject of Marks & Spencer (having replaced two thirds of their territory on the game board with something more distinctive) one thing that needs to be discussed is the notion of importing foodstuffs from China. With the apparently endless succession of food scares and scandals coming out of China, food from that source is thankfully rare in the UK. The Food Storage & Distribution Federation are mentioned on a few cards, but these can be picked out and disposed of easily enough. One of them is a bit silly anyway, in that it implies that all containers in the game are temperature controlled.

None of these gripes should be seen as insurmountable problems with Business of the Move: unless you’re competing in the world championships[1], you should always feel free to fix anything that you don’t like in a board game. Out of the box, Talisman (mentioned earlier) is a pretty awful game – but if you throw out certain cards that wreck the game mechanics and make a few other tweaks, it can be improved no end. Few people play Monopoly according to the rules as written. Similarly, Business on the Move is a very promising kit of bits: it has a few quirks, but nothing that can’t be fixed with ease.

Surprisingly, I have been unable to find a web-based forum that allows owners of the game to share experiences, and perhaps resolve the occasional ambiguities that are found within the rules. Perhaps the Very Enterprising Community Interest Company don’t have the resources to moderate a forum, but it seems a major oversight in these days of Web 2.0. (If you can find an online community that discusses how to get the best out of the game, please let me know?)

Meanwhile, I think one of the best ways to resolve the limitations of the game will be to have the students take care of them. For example, after introducing the students to the game, why not turn them loose with instructions to write rules for a game variant of their choice?

One thing a modified game might benefit from is rules for vans. If you’re playing the variant where you get to split a container into three pallet-loads for different recipients, it’s a shame that you’re left delivering those pallet loads using the standard truck: a fleet of vans could be made to dash off in all directions. Other student projects might add a set of rules that address warehousing, or replace the simplistic rules for insurance with something that teaches more about risk and decision management. How about adding a ‘nearshoring’ option whereby the player gets to consider procuring goods from the European Union – less profitable but with items available sooner? You could have UK manufacturing play more of a role, too.

Business on the Move needs a few tweaks to really get the best from it, but it’s oozing with possibilities.

[1] If ‘World Championships’ and ‘board game’ seems too embarrassingly nerdy, bear in mind that the Monopoly World Championship is played with real money – winner take all.