Things in the UK haven’t changed this much, this fast, since the Second World War. Historians, economists and other scholars will sift through the wreckage of 2020 in due course and no doubt there will be interesting things to discover – but supply chain people are generally less interested in history; more interested in problem-solving.

There was a time when a significant chunk of my research was about scenario analysis, so let’s look at our current COVID-disrupted circumstances through that lens. What trends are developing? What behaviours contribute to the outcomes we are seeing? Already, we know quite a lot. If we can ease our way past day-to-day concerns about shortages of toilet paper and bread flour, it’s reasonably easy see some things that are happening. There’s no need to wait until you’re told about them on the evening news… and in any case the evening news isn’t going to tell us the things that affect us because the “Big Story” is drowning out all the little ones.

For this reason, I chose to look at a more obscure set of winners and losers. My list isn’t meant to be exhaustive, but simply illustrative. I’ll leave it to professional journalists to report on the main issues, like a loss of faith in the World Health Organisation… mass unemployment… calls to boycott Chinese goods… but where else are we seeing changes?

Winner: Home Economics (domestic science)

Winner: Home Economics (domestic science)

A few days after panic-buying gripped the nation, a lot of food was thrown out. It appears that many people simply didn’t know what to do with the food that they had managed to buy. The government told us that it should be possible to get three meals out of a chicken but they may have been overestimating the culinary skills of British public. (That same public who mourned the closure of fast food outlets to an almost comical degree.)

As a school subject, home economics has been denigrated for years. It was a “practical subject” – which is a coded way of saying that high-achieving kids aren’t encouraged to study it. Home economics often came with an undercurrent of sexism, too. Add in the fact that the facilities and materials made it an expensive subject for schools to offer, and no wonder it was run down… but now we discover that we needed it. With food in short supply today, it’s clear that a little more education in home economics would be useful. Each time I discover that some ingredient has gone off before I used it, that’s an argument in favour of domestic science education: I expect that we will see a resurgence of this subject in the post-COVID world.

Loser: Cash

Loser: Cash

Nobody wants your money, anymore – in case it has invisible cooties on it. It’s a blow for older generations who aren’t entirely comfortable with online shopping and contactless payment as they find that paying with legal tender is positively discouraged.

The governments of many countries have been trying to wean people off certain low-denomination coins for years, on the grounds that they cost more to make than they’re worth. In fact, a lot of governments might secretly like the idea of an entirely cashless economy because it would put a serious dent in the underground economy. Cash transactions have been under pressure ever since banks made it hard to withdraw cash where this had traditionally been the means for companies to make payroll.

Could a pandemic push some countries toward a future of all-electronic funds? It probably won’t happen right away, but the decline of coins and banknotes has definitely been hastened by COVID-19.

Coins were introduced around the 6th century BCE, first being minted by the Lydians, according to Herdotous. They’ve had a good run. [image: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc.]

Winner: Long-life food formats

Winner: Long-life food formats

As a nation, we’ve become accustomed to the idea that you can pick something up on the way home from work. At a time when so many of us are no longer travelling to work, those mini-supermarkets located on railway station concourses aren’t very useful. Also, visits to supermarkets of all sizes are much less pleasant now. Whether you’re going to queue round the block to enter the premises, get into a fist-fight with your fellow shoppers, be sneezed on or simply find that the item you went for isn’t in stock, nobody wants to do this more often than they absolutely have to.

All of a sudden, we’ve been reacquainted with the value of tinned, frozen and dried food. Breaded goujons from the chiller cabinet were all very well in the pre-COVID world, but now we want good old fish fingers. They keep for months and you can easily find room for two dozen of them in your freezer. I suspect that even when everything is “back to normal” a lot of us will tend to keep more food in stock, and that means more long-life food; less chilled and fresh. This would be a good time to buy shares in a cannery.

Loser: Horoscopes

Loser: Horoscopes

Aside from the obvious problem, that none of the feted astrologers managed to predict the COVID-19 crisis… the big problem facing astrologers now is coming up with twelve different things to say to their various subscribers, day after day, when every day is much the same for everyone.

It’s ten years since all the woo-woo “sciences” (palmistry, psychic readings and so on) received a mortal blow from EU consumer protection regulations requiring them to make clear that the services they offer are for entertainment only and not experimentally proven. Perhaps the unforeseen circumstances we are now living through will finally consign the notion of Messages from Beyond to the ash heap of history.

Let’s hope so.

Winner: Useless CEOs

Winner: Useless CEOs

If you’re in charge of an ailing company that’s been on a downward spiral for years, this is a great time to shut it down. Right now, you have the best possible chance of abandoning the mess that you’ve created while preserving the two things that are most important:

-

-

-

-

- Your “personal brand”, and

- Your ego

Useless CEOs had to do just two things. Job one was to read the morning papers – the same ones that you and I look at. Job two was to use the last ten weeks or so to formulate strategies that would anticipate how their business could continue, even thrive, during a pandemic. For this, they had a pretty good foundation, based on what had already occurred with SARS, Swine Flu, Ebola… so are we really going to allow them to act all surprised and disappointed when the business they run goes off the rails?

Not to worry, bad CEOs: it can’t possibly be your fault that thousands of people are losing their jobs. It’s COVID-19, innit? And maybe BREXIT, too. At last, a way out of that hole you dug for yourself by selling off all your company’s assets: simply wind up the whole thing and make sad faces. Spend more time on your yacht, because you’ve “earned it!” Useless CEOs sail away into the sunset with a big win this year – and perhaps quite a lot of taxpayers’ money as well.

Loser: Charity shops

Loser: Charity shops

At a time when people are feeling nervous even about the brand new items that they’re getting in the post, who’s going to want to buy second-hand ones? Moreover, what volunteer is going to be prepared to pick through the items that get donated?

An additional problem for charity shops is that one of the first things we all did under lockdown was to have a big clear-out. This may have made our homes more habitable, but it also led to virtually everything going into landfill. Charity shops have lost out in a big way – and eBay isn’t looking very attractive, either.

Winner: Our Homes and Gardens

Winner: Our Homes and Gardens

Most of us have been spending a lot more time at home and this has led us to think about making that space better. Most DIY shops remained open in some form because house repairs were considered essential. Many customers will have found it necessary to use “click and collect” or arrange home delivery, but a lot of home improvements have been going on.

We’re on the horns of a dilemma here. Garden furniture may not be essential, but keeping some fragment of the economy ticking along at this time isn’t exactly a bad thing. So should you order items for home delivery, or not? Online shopping is causing people who work in fulfilment to go into a workplace where there are significant concerns about their safety… but this can only be considered on a case-by-case basis. Individuals and (where permitted) trade unions will have to take action here, because customers simply don’t know enough about working conditions.

Until we’re asked to show restraint – or until online shopping for non-essential goods is banned outright by those in charge – I’d say you can make purchases for home and garden a matter for your conscience… perhaps informed by articles such as this one.

Loser: Anybody with a strong opinion on BREXIT

Loser: Anybody with a strong opinion on BREXIT

On both sides of the UK’s 52%-48% divide, those with strongly-held opinions were counting the days until (they hoped) they could say “I told you so!”

Whatever happens now, BREXIT is small potatoes. These weeks of lockdown and social distancing have done far more damage to the economy than even the hardest of hard BREXITs could have done. If BREXIT is delayed, that’s not Boris’ fault but COVID-19’s. If the United Kingdom is debt-riddled and austere for years to come, that’s not Boris’ fault but COVID-19’s. Even if the European project itself fails (this piece suggested a rift was developing between the financially prudent member states and the more spendthrift, southern ones) it can’t be said to be a consequence of BREXIT: with COVID-19 in the room, everything else gets put into perspective.

Loser: my Barber

Loser: my Barber

I appreciate that an anecdote doesn’t constitute evidence of a major trend, but consider this as indicative of damage to the service economy as a whole.

When other people were still worrying about pasta and toilet paper, I was buying hair clippers. We logistics people like to look ahead… and hair is going to keep on growing, lockdown or no. In fact, lockdown is the ideal time to experiment with a home-grown haircut because (a) it’s likely to be better than nothing and (b) even if it’s horrendous, who’s going to see it? By the time this lockdown ends, I’ll have had several home haircuts and perhaps each can be expected to be a little more proficient than the last. If the end result is actually sort of OK, given that I’m a grizzled old geezer with no particular interest in being fashionable… as far as my barber is concerned I might as well have died in the pandemic: he might never see me again. This is a small but more-or-less permanent knock to the service economy. Extend that across the nation, with similar stories from other sectors, and you have a recipe for a very weak recovery indeed.

Winner: reshoring

Winner: reshoring

This particular piece of management yuckspeak is more commonly found in my supply chain strategy module, where it refers to bringing back that which was previously offshored for economic reasons. Can it be made to work? Well… maybe. Consider how all the shops ran out of paracetamol: apparently a vital thing to have in the fight against COVID-19. Imported, store-branded paracetamol was dirt cheap, but the spike in demand that we saw with COVID-19 showed how foolish it was to cede control of manufacturing. We are seeing the same thing with shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) – and people are dying as a result.

Governments must now be thinking about rolling back on globalisation – and stories like this will hasten the process. Offshoring was about price, but reshoring is about the far more important issue of control. In the same way that governments have sometimes requisitioned ships and aircraft in time of war (with consequences for the registry system, leading inevitably to higher prices) we can expect to see governments move to secure closer control of key industries… which means, whether through tariffs or incentives, the newly-strategic apparatus of COVID-era healthcare being brought back to our own shores.

A good time to be in UK manufacturing, perhaps… if the overall economic depression doesn’t bite too hard, for too long.

Loser: the Police Service

Loser: the Police Service

Take a part of the machinery of state that has been run down for decades – made up of staff who are no less likely to become infected than anybody else – and give them vague instructions at short notice, requiring large-scale deployment against “ordinary people.” (Possibly stupid people who think that what a nation on lockdown really needs is bouncy castles… but not previously those thought of as members of the criminal classes.)

This is a recipe for disquiet: you leave the police to interpret their unclear instructions and deploy their inadequate resources as best they can, handing out penalties that quite possibly wouldn’t stand up in court, if challenged. The result is resentment that could last a generation – or even overturn the policing by consent model itself.

Winner: the Study of Pollution

Winner: the Study of Pollution

We only rarely get a chance to see what our skies used to be like, and that’s important in establishing a baseline. It happened in North America after 9/11 and in Europe after the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010, but the current situation sees the number of flights sharply reduced with no clear end in sight – and cities normally known for smog are much cleaner, too.

Will climate scientists find this lull useful? Certainly. Will ordinary people notice the improvement in air quality? Yes – if they’re allowed out. Will they value the improved air quality so much that they press for change, later on? Probably not: more likely we’ll be so glad to have jobs to go back to that we’ll accept a return to the bad old days of traffic jams and sulphur dioxide.

The study of pollution is the winner here, not the fight against pollution itself.

Loser: Air Travel

Loser: Air Travel

A complicated set of businesses collaborate to offer air transportation, many working in the background to make it possible. All stand to lose out while ’planes are grounded. The usually cash-positive business of aviation has a huge wage bill and expensive assets sat around, depreciating or requiring lease payments.

Longer-term, businesses that have had to make do with videoconferencing in place of face-to-face visits might decide that it’s actually worked out pretty well, with the result that business travel volumes never fully recover. The problem here is that business travel was always far more lucrative for airlines than carrying the far more numerous hoi polloi at the back of the ’plane. Even if we, the holidaying public, decide to throw caution to the wind and start holidaying in far-flung places straight away (which is unlikely) prices are likely to be higher.

A complicating factor is that some airlines have acted disgracefully, not refunding passengers’ money for cancelled flights but offering credits against future flights… which might get them one more flight, grudgingly, but is likely to have put a huge dent in customer loyalty.

For manufacturers, COVID-19 comes after Boeing’s disastrous time with the 737 MAX (still grounded worldwide; still inspiring no confidence whatsoever) and Airbus’ failure with the A380 (passengers love them; airlines don’t know how to fill them; Airbus never sold enough to cover the huge cost of their development). If the demand for air travel is depressed by even five percent overall there are going to be a lot of slightly-used aircraft for sale, resulting in a very bad time for aircraft manufacturers and their supply networks, for years to come.

Question Mark: the Food Industry

Question Mark: the Food Industry

This is a tricky one. On the one hand, after those scenes of empty shelves and people fighting over the last jar or hotdogs we’re all so absurdly grateful to have food of any kind that we aren’t looking much at the prices. They’ve crept up… maybe up to the point where farming becomes a secure, long-term business proposition. That can’t be bad for the industry.

On the other hand, farms will find that they are desperately short-handed. In any other year, growers could expect to hire an army of workers from eastern Europe. This year, those people simple aren’t here. This raises the prospect of a double-whammy: reduced supplies from overseas – many of the nations we usually import food from now have virus worries of their own – while locally grown supplies might be left to rot in the fields due to a lack of adequate labour. More reasons for prices to rise and shortages to manifest themselves.

We might also see citizen volunteers (or temporary workers) on the land – although many will be surprised at just how hard the work can be. We might even see a benefits system shake-up whereby those who are unemployed or “furloughed” are found work in the fields. This new ‘Land Army’ is just one example of how current policy is being shaped by things that occurred in the Second World War.

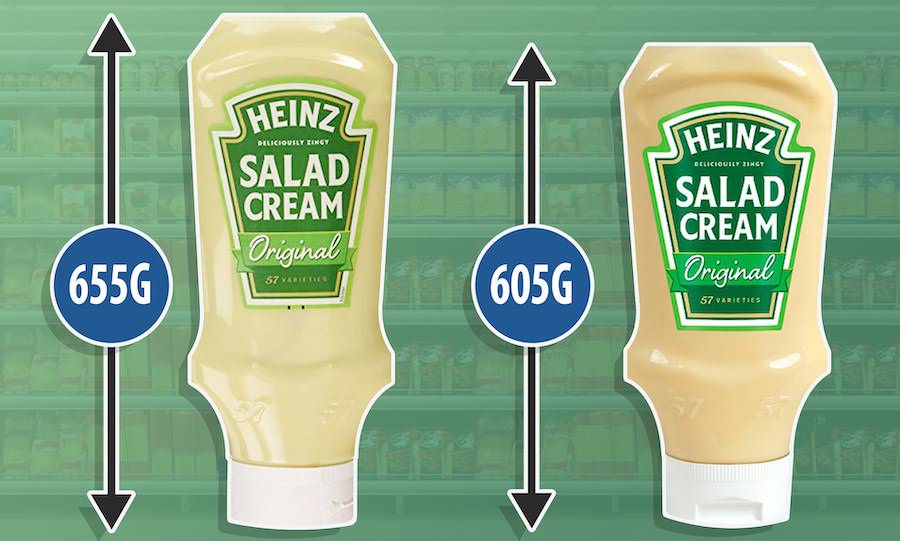

Loser: Variety

Loser: Variety

At a time when supermarkets were largely unable to cope with the surge in demand, we saw an interesting new development. UK supermarket chain Morrisons was one of the first to offer a no-frills food box, described thus:

“Our boxes contain a selection of items based on our current availability of products, therefore we are unable to specify exact contents of each box. You will however receive a variety of different foods in each box. Typically this box should feed 2 adults for one week.”

Remember when shopping involved a choice between three or four different brands for any particular item? If you wanted pesto… did you want a premium brand? Economy? In a jar, or fresh? Now we get food for two adults, for a week, meat-eater or vegetarian… no further details.

This somewhat resembles the situation in World War II: always a net importer of food, the UK began offering undifferentiated, commodity products within the rationing framework. Tea was no longer Brooke Bond, Lyons or Tetley: it was just “tea”. (It was my maternal grandfather’s job to blend tea from what was available, in fact.) Likewise chocolate ceased to be Bourneville, Fry’s or Dairy Milk but just chocolate (two ounces per person) and bread would become the standardised National Loaf, too.

For supermarkets, perhaps the present reduction in variety will be found to be a good thing. They might actually seek to streamline the vast array of Stock Keeping Units that they carry, when all this is over.

Question mark: the UK National Health Service

Question mark: the UK National Health Service

It’s hard to know quite what to expect in the future of healthcare. Elsewhere this will be examined in its own right, no doubt, but let’s try a quick look. On the one hand, the National Health Service is garnering colossal amounts of goodwill. Foolish indeed will be the politician who fails to acknowledge this: the NHS can expect increased funding in the years to come.

Perhaps we’ve become very complacent about the National Health Service, though. Politicians of all flavours had routinely described it as “excellent” as a matter of course… until COVID-19. All of a sudden, we were worried that it wouldn’t cope. Italy, we were told, had an excellent healthcare system but one that was buckling under the unprecedented strain placed upon it in early 2020.

Perhaps the NHS was most enviable in terms of its pricing model, rather than its sheer capability. This is a healthcare system that most of us pay almost nothing for (taxes, of course, but after that most British people of working age pay only for dental care and a contribution towards prescription charges). It really is exceptionally good value – but is “healthcare that is a bargain” top of your wish list right now? Maybe not.

On the downside, who is going to want to work in this hypothetical, better-funded health service? Having read news articles about thirteen-hour shifts; having seen photos of what long-term wearing of protective equipment does to the skin; having counted the casualties among those on the front lines… I sense a recruitment crisis.

At best, we will see a hard-bitten, better equipped NHS in place to support us through subsequent waves of this pandemic and others to come. Then there’s the elephant in the room: that COVID-19 and associated disruptions to “business as usual” in our care system could significantly reduce the number of old and infirm people – those who have in recent years been described as representing a “demographic timebomb.” It’s not a nice thought, but 2020 might do a lot to defuse a timebomb that a succession of administrations have failed to address.

Winner: Laptops

Winner: Laptops

In recent years, IT managers have typically required their staff to make do with some pretty awful laptops. Let’s be honest: if you didn’t work for a ‘hipster’ startup and you weren’t the boss, you probably had something clunky and outdated. (Students routinely have better laptops than their lecturers, nowadays.)

Then came COVID-19. All of a sudden, staff were expected to join meetings via videoconferencing and the full horror of those laptops became plain to see. From the dim, grainy cameras on the ageing ones to the dreadful audio on their cheap replacements, conferences up and down the land echoed to the sound of “Uh… sorry… can you repeat that?”

Chinese factories might be in disarray or shut down entirely, but IT managers are spending like they haven’t done for a decade. Windows laptops have exhibited a race to the bottom on quality in recent years, with £700 being considered “a lot” to spend on a member of staff, but for a little while at least, that’s likely to change.

Loser: cities

Loser: cities

Nothing in recent years has done more to discourage city living than COVID-19. Imagine that you were one of the people who had paid top dollar for a small city apartment: it might once have seemed that you were “at the heart of things,” but now there’s no upside to city living: just a lack of green space and difficulty maintaining safe social distancing.

Outside the city, people enjoy more spacious homes and fewer arguments as a result. They relax in their gardens; a short walk gets them out into the countryside. They are surrounded by farms, confident that they won’t have any real food worries.

Expect those inner city apartments to have lost at least £20,000 in value when moving home becomes possible again. City folk who also own a holiday home in the countryside have had it worst of all, discovering that the locals have made them distinctly unwelcome when they sought to escape the disease… for fear that they brought it with them.

Winners: David Mitchell and Robert Webb

Winners: David Mitchell and Robert Webb

In 2009, television comedy sketch show That Mitchell and Webb Look featured a recurring item in which we saw The Quiz Broadcast, a game show set in a post-apocalyptic Britain that had been wrecked by a mysterious happening known only as “The Event”. As contestants competed for firewood, the quiz show host constantly reminded viewers to “remain indoors!”

This has been trending on social media in a big way, with people drawing parallels to their present-day circumstances. The comments section is stuffed with variations of “years ago, this was a comedy sketch: now it’s a documentary.” That’s not quite true… but if it earns Mitchell and Webb a well-deserved second look from new audiences, well and good.

—

Now wash your hands.

Winner:

Winner:  Loser: Cash

Loser: Cash

Winner: Long-life food formats

Winner: Long-life food formats Loser: Horoscopes

Loser: Horoscopes Winner: Useless CEOs

Winner: Useless CEOs Loser: Charity shops

Loser: Charity shops Winner: Our Homes and Gardens

Winner: Our Homes and Gardens Loser: Anybody with a strong opinion on BREXIT

Loser: Anybody with a strong opinion on BREXIT Loser: my Barber

Loser: my Barber Winner: reshoring

Winner: reshoring Loser: the Police Service

Loser: the Police Service Winner: the Study of Pollution

Winner: the Study of Pollution Loser: Air Travel

Loser: Air Travel Question Mark: the Food Industry

Question Mark: the Food Industry Loser: Variety

Loser: Variety Question mark: the UK National Health Service

Question mark: the UK National Health Service Winner: Laptops

Winner: Laptops Loser: cities

Loser: cities Winners: David Mitchell and Robert Webb

Winners: David Mitchell and Robert Webb